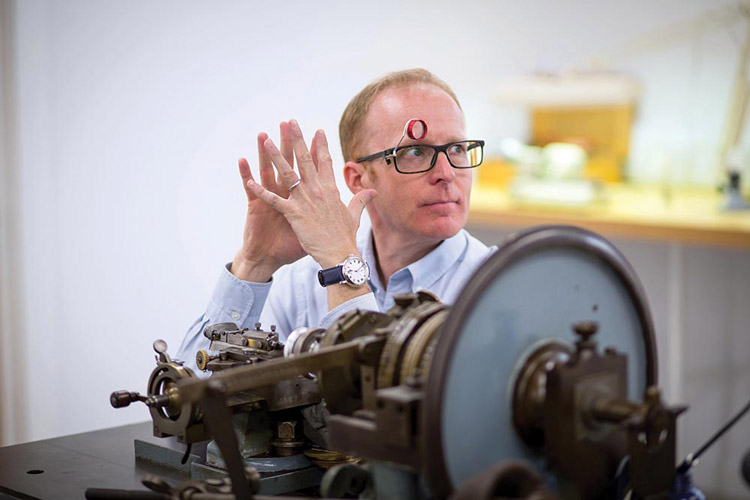

Roger W Smith: reviving British haute horlogerie

In this new series that will be featured every month, “Day & Night” focuses on individuals who have impacted the world of haute horlogerie positively… This month, we look at the life and growth of Roger W Smith, OBE, independent British watchmaker who is intent on putting Britain back on the horological map

Accolades such as ‘watchmaking wizard’ and ‘greatest watchmaker of the modern era’ are freely sprinkled when Roger W Smith is the subject of discussion. “Day & Night” magazine felt privileged to sit down with him to dig deeper into the man behind the legend.

Bolton, Manchester, UK – late 1970s to early 1980s

The woods on the outskirts of Bolton, a small town with a population of less than 200,000, was the favourite playing grounds for a young boy, Roger W Smith. Roger (b. 1970) is the son of a doctor, a rheumatologist. Life was good, and Roger did all the usual things boys did – played outdoors a lot, fell off his bike a lot, and generally made a nuisance of himself in the usual manner of young boys. Those were days of play and exploration. The family lived on the edge of the countryside and thus enjoyed a very outdoors lifestyle. Schooling was fun, though little Roger never really excelled at school as he never really understood school or the point of schooling. He drifted through the years of school as a lot of boys do, with no great purpose or show of future genius. But all that soon changed

Manchester – 1986 to 1988

Dr Smith, meanwhile, perhaps thanks to the perspicacity of a loving parent, and watching his son’s interest in the practical aspect of making things, his frequent preoccupation with a long-case clock they had at home, and in how it worked, gently nudged his son in the right direction. Guided by his father, Roger enrolled in a horological course at Manchester in 1986.

This course, for him, was the best education that he could ever have had; it was very practical, vocation-oriented. Suddenly, he was in an environment where he was allowed to use tools; he and his classmates were making things and using hand files, saws, and other hand tools. It was more fun and far better than studying or memorising. It was very hands-on, and he just loved it and excelled at it.

The course was based on British horology, and it was designed to give students a practical flavour of all kinds of clocks, such as turret clocks and so on. The idea of the 3-year course was to give a student an experience of using their hands, working with hand tools, and building up a base of knowledge on which they could go out and specialise in whichever area they wished to. It also included working on restorations.

During the course, Roger took a part-time job with a company based in Bolton; it was a service centre for Heuer watches (Heuer at that time, not TAG Heuer). It was great because he was getting experience at a service centre, which he not only enjoyed it but where he also learnt a great deal about watches. He worked there for around three years, some as a part-timer when he was in college and later as a full-time employee. He eventually left when he realised that he was not using his handcrafting skills the way he wanted to.

During his time at the horological institute, he met watchmaker George Daniels – a meeting that was to change his life. George Daniels, CBE, FBHI, FSA, AHCI, was a horological legend in his own lifetime, and is best known for his creation of the coaxial escapement, which has been used by Omega for their collections since 1999. Daniels had an incredible impact on young Roger; here was a man who designed and made a complete watch by himself – from start to finish. George, who was by then a very well-known watchmaker, had visited the college and spoke to the students about his watchmaking experiences and how he built his individual handmade watches. This concept lodged itself in Roger’s head and he started to think about a future in watchmaking.

Isle of Man – 1989

Eventually, when Roger was 19, his increasing interest led to him writing to George, who lived in the Isle of Man, asking him if there was a possibility of being apprenticed to him. George wrote back saying it was not possible, but that Roger was welcome to visit him. An eager Roger visited the Isle of Man and George took him on a tour of his workshop and talked about his watchmaking. He told Roger, “Look, if you want to make a watch, you have to teach yourself. I can’t teach you. You have to be personally driven…and be able to make your own home-made watch.” The information was easily available; now it was up to Roger to go after it. George had authored a book titled “Watchmaking,” which provided a start. That was the beginning of Roger’s watchmaking journey.

Bolton, Manchester – early 1990s

It was a long learning process; Roger was still living with his parents who had let him modify their garage to accommodate a small workshop. He was still working with TAG Heuer (TAG Heuer by then) and was obsessed with the idea of making a complete watch with his own hands. Dr Smith lent Roger a little money to buy a lathe and other basic equipment. Roger quit his job and started doing some trade repair work for jewellers; he was working 2-3 days a week for them and the rest of the time, he devoted to building a pocket watch.

That first watch took him a year-and-half to make, with absolutely no guidance from anybody. At that point, it was just Roger and his copy of George’s book “Watchmaking” – his bible and guide to building a pocket watch. He followed it as best as he could and, 18 months later, had made his first complete watch. A hopeful Roger took it to George to get his approval but was told that it looked too hand-made. A gruff George said, “Congratulations, you have a watch that works and ticks but now you need to go and focus on the minutiae of watchmaking – the skills.” Roger was told that the watch needed to look “created” and not “hand-made.” The problem with the watch he had made was that George “could see the hand of the watchmaker in the watch” – something that was a big no. A sorely deflated Roger left the Isle of Man even more determined to prove that he could make a watch.

Isle of Man – mid 1990s

Five years later saw Roger walk up the driveway of George’s home, full of trepidation. This was the moment that would decide his fate. It was the culmination of five years of hard work, repeatedly making a watch, obsessing over the quality and craftsmanship, and continually refining his work. If George didn’t like this watch, perhaps Roger’s dreams of watchmaking should be put aside.

The past five years had been a painstaking process of creating a watch that could meet George’s exacting standards. Roger had also been repairing watches of other brands, which helped him earn the money to pay off his loan and left a bit for some recreation and fun. This was his second pocket watch and he made it around 4 times over the five years, refining it over and over. At the end of the first year, the watch was working but then the components that Roger had made at the beginning of the year felt of poorer quality to his growing sensibilities. He would go back to the beginning of the watch and remake it. That process continued and continued over a five-year period, and it eventually got to a point where Roger knew he couldn’t improve any more. He felt that he had reached the level of watchmaking that would match George’s demands.

Fortunately, the meeting went better than Roger expected; George fully approved of the watch. He said, “Congratulations, you are now a watchmaker.” For Roger that was an incredible moment, a vindication of 7 years of hard work. But then, George added, “Now you need to develop your own personal style.” That was the next phase and the beginning of another long journey.

Isle of Man – 1998 to 2001

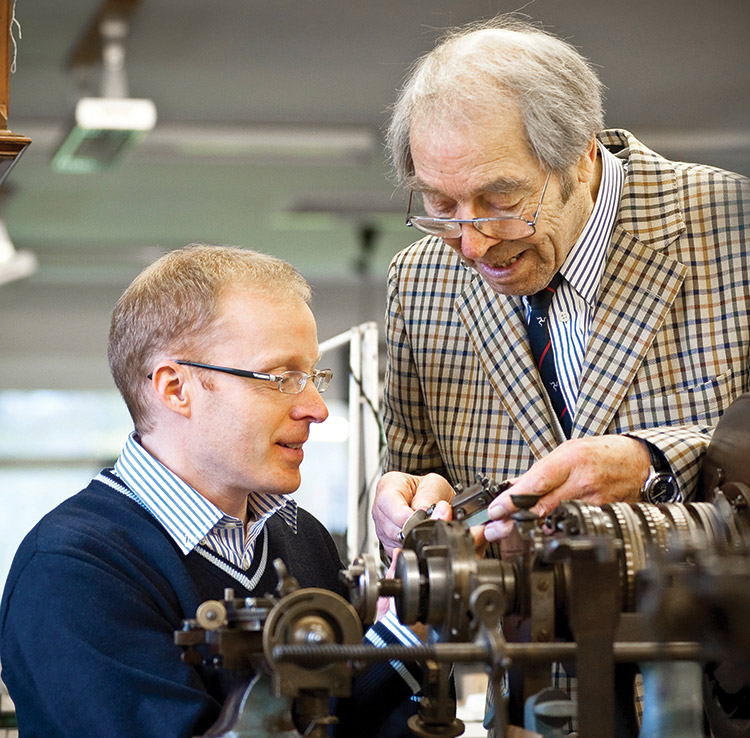

In these years, Roger grew more skilled in what he terms “The Daniels Method” that defines the way George worked. George would design a watch and make it in its entirety. A very unusual approach to watchmaking, it was born out of the fact that George had ideas to improve the mechanical timekeeper. But the watchmaking industry in Britain had disappeared; there was no watchmaking left even though London and Paris had played a historically important role in watchmaking. The British were not prepared to industrialise the watchmaking trade. George ended up learning all the skills to create a complete watch by hand – creating the dial, hands, case, and everything else; mastering 34 skills that George deemed requisite for creating a watch. Roger named it The Daniels Method and it is still followed in Roger’s workshop – one man designs and makes the watch, from start to finish.

Roger went to work with George in 1998 on the Millennium Wristwatch Project and worked with him for around three years. For Roger, it was incredibly amazing experience; not only did Roger have his book, but he had the man himself for that extra support. George was a brilliant teacher and was able to fill in all the gaps that were needed for Roger to become a master watchmaker.

Isle of Man – 2001 till date

Around this time, Roger bought a house on the Isle of Man – a small cottage where he created a small workshop. Still single, he had the house to himself and the time to devote to his fledgling enterprise. He began by creating his “Series 1” of wristwatches. At that point, there was not any interest in pocket watches, which George had predominantly made till then and so he started making wristwatches. It was a daunting process as he was once again starting from the scratch. This meant trying to find a market for his work, trying to connect with co-actors, and designing a wristwatch, which he had never done before.

Series 1

Transitioning from a pocket watch to a wristwatch is a massive endeavour, and everything had to be done by hand. Roger had no CNC equipment at that time; it was a huge challenge, but he learnt a lot in the process and ended up making nine of those early pieces – all of which were sold.

Those early days were a real challenge and a terrifying period for Roger, who led a hand-to-mouth existence then. Roger didn’t make any money out of that project. He was finding his way, learning how to speak to clients, how to communicate to journalists – learning how to tell his story, which was still developing. It was a challenge financially, but it built the base for where he is today.

The original Series 1 had a rectangular case, unlike the current timepieces of Series 1 that feature a round case. At the time Roger was designing the original Series 1, he was blown away by A. Lange & Söhne’s Cabaret, which impressed him highly with its construction, mechanism, dial, and other features. Very much inspired by this newly reborn brand that was doing something very different, Roger felt that if he could design a rectangular-shaped watch, it would perhaps draw some attention to his work.

Series 2

Series 2 debuted in 2006, five years later – again, a big moment. With Series 1, Roger had produced some components, but had bought some others as he just didn’t have the knowledge to make a complete wristwatch. With Series 2, he was determined to create the whole watch completely in-house. Getting to that point was a huge challenge and it took five years. Series 2 is the biggest milestone for Roger’s eponymous brand. Roger muses that it was perhaps then that his aesthetics really came together. He had been working on the aesthetics and the sense of proportion and he believe that Series 2 is when a lot of his ideas were really honed. Of course, his experience with Series 1 experience had led him to this point.

Skeleton Series 5

After unveiling Series 3 and Series 4, Roger launched his iconic Skeleton Series 5 in 2016. He describes Series 5 as an ongoing process. On being asked about when we could expect an updated version of Skeleton Series 5, he says, “I remodelled the Series 5 for an open dial in 2015 and we are still delivering those pieces. The thing is that I will never stop making any of my watches – all the Series beginning from 1, because I have put in so much effort in creating those watches. We make a very limited number; we create only 18 watches a year. But the problem is that because of our limited production, the waiting period for our watches goes into years – sometimes 8 or 10 years.”

One continuous problem that Roger faces is that demand far outstrips supply. He is studying the feasibility of increasing his annual production to 24 pieces, but he is also determined to hold onto his self-determined quality and standards. He is aware that it is a difficult proposition and is prepared to deal with it at some point. Currently, he employs 15 people, 10 of whom create watches. Though he employs people straight from college, they have to have some basic watchmaking knowledge. He now heads an amazing team that is quite young.

The website of Roger W Smith The Watchmaker describes that it is “applying next generation science to what has always been regarded a traditional art form.” Roger expounds on that. “We use the co-axial escapement, which is the lightest one and the most advanced in terms of technology – the most technically efficient escapement available currently. We are also looking at nano technology to reduce friction and replace the oil that we find in the common wristwatch. While on the one hand, I am traditional in my approach to watchmaking, I am also fascinated in trying to improve the life of a mechanical timekeeper – in improving the quality, construction, and efficiency of the mechanism.” He is also working with the Manchester Metropolitan University on the development of nano technology.

Though George Daniels has had massive influence on Roger’s oeuvre, one major difference is that George’s creations all featured single-component dials, while Roger’s dials are multi-component. Roger explains why: “When you are making the dial of a pocket watch, it is bigger and easier to engine-turn. When I started making my first rectangular Series 1, I was seeing some engine-turned dials coming out from Switzerland that were of superb quality. I realised that perhaps there was some CNC and other types of processes being used. I had to somehow compete, but I still wanted to use the traditional engine-turning techniques. I realised that if I wanted to do that on a wristwatch, I could not attain the quality that would be comparable to what was coming out of mass production in Switzerland. I realised that if I could fabricate the dial from components, I could greatly improve the quality of the dial.”

Roger is intrigued by the storied past of the British watchmaking industry. Britain led the world in watchmaking from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Finely made pocket watches and clocks were being shipped from Britain to places around the world. “That trade disappeared because the people who were controlling the trade refused to adopt industrial methods of manufacture; they were still keen on building traditional watches. We have made a beginning, but it is still very small.”

Roger thinks that British watchmaking is going to go places in the future, but it is going to take a long time. “We are right at the beginning of a new journey for British watchmaking. We have lost the skills, the base knowledge. We can all buy the same equipment from Switzerland or Germany, but we need to learn those skills and training, and that is going to take time. It may take anytime between 20 to 50 years before we see something happening, but I hope it will be a gradual trajectory as people start to try picking off the easy wins.” He adds, “For instance, all we need is for someone to start making watch cases and it will be a beginning. It will not be what it was; it will also never be a replication of say the Swiss watch industry. We have got to do something different; there is no lack of creativity in Britain, and I think it is already beginning to shine through in the small sometimes micro-brands that are starting up here.”

Meanwhile, he is full of admiration for haute horlogerie creations from other countries. “Germany and Switzerland are doing an incredible job of making some amazing watches. They have perfected their art over so many decades and I am very impressed with what they are able to achieve.”

Roger W Smith’s creations are available in the region at Perpétuel on https://perpetuel.com/